|

|

|

|

Lonnie Youngblood Interview 1996 |  |

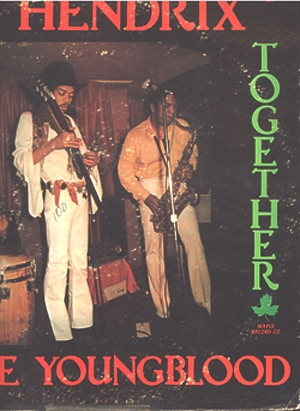

By Frank Moriarity Fans of Jimi Hendrix are no doubt familiar with the name Lonnie Youngblood. In fact, the odds are good that most of Jimi's followers have several albums or CDs in their collections containing material from Hendrix's first professional recording sessions - sessions spent backing sax player/vocalist Youngblood in the recording of thirteen rhythm and blues tracks. The fact that the sessions took place late in 1963 is generally accepted, but beyond that little else has been revealed about Jimi's time with Youngblood or the professional career of Lonnie himself. The fact that Youngblood has not been interviewed in depth about this period has doubtlessly contributed to the haze of mystery that cloaks one of the significant events in the history of rock - Jimi Hendrix's recorded debut. In the summer of 1996, I had the opportunity to speak at length with Lonnie Youngblood. Youngblood was performing at a restaurant - the well-known soul food establishment Sylvia's - at 126th and Lennox Avenues in Harlem. After I traveled to Harlem for an initial meeting, Lonnie was kind enough to meet with me in person and speak on the telephone several times during August, September, and October. Personable and a very youthful 55 years of age, Lonnie Youngblood looked back on his days with Jimi Hendrix - then known as Jimmy James - and on his own fascinating rhythm and blues career that has spanned over four decades. Youngblood was born on August 3, 1941, in southern Georgia. As he grew up, Lonnie soon realized he had an attraction to the saxophone - thanks to the music of the one of the greatest stars of the 1940's. Stylistically Youngblood patterned himself after one the greatest sax players ever, and a man who hired Jimi Hendrix to play in his band in 1966. “I used to do the King Curtis licks, that was my thing,” Youngblood notes. “I loved King Curtis, too - we became the best of friends. We were rivals, but we were great friends. I feel like today that I have not even gotten to the point where he was when he died.” With his reputation cemented in the Harlem community, a brief period in the army after being drafted came to an end with Lonnie being welcomed back into Harlem’s musical community in 1963. And there he found Jimi Hendrix, who had finished his own military service the summer before. “After I came back I met Jimi Hendrix. He came on into New York, and he was working with a group,” Lonnie explains. “I had been drafted into the Army; I came out of the Army and I was looking for something. So I met these guys who I knew before I went into the Army. They said, ‘Come on and join us, Lonnie - we’ve got this great guitar player.’ So, I said, ‘OK, man, I’ll come and hear you,’ to see what I liked or what I could do about it, you know? And I went, and that’s where Jimi Hendrix was, playing with this band.” And who was leading this band? “At the time, it was Curtis Knight,” Lonnie answers. “Curtis was the band leader, and he was playing rhythm guitar. But he couldn’t really, He wasn’t a very good musician at the time. He was more or less a hindrance to the band. After a while he sort of split the scene, so it was an opportunity for me to front my situation. So I just enticed the guys to go on with me.” The possibility of an early, brief association between Curtis Knight and Jimi Hendrix late in 1963 has not been raised before, although Knight did write in his 1974 biography Jimi: An Intimate Biography of Jimi Hendrix that Knight arrived in New York early in 1963 and immediately began working at breaking into the music scene. Although Knight has claimed that he first met Hendrix in 1964 outside a recording studio in a New York hotel lobby, if an early Knight band was taken over by Youngblood in 1963 perhaps Knight would not be enthusiastic about bringing up unpleasant memories. “That band had problems - and you know how bands have problems,” Lonnie continues. “So they didn’t want to break up, but they wanted somebody to lead them. And I said, ‘Well, I ain’t got no money so I can’t lead no band.’ Jimi said, ‘Man, I don’t care, I just want to play.’ So I said, ‘Well, OK then, So I got us a couple of jobs. A couple of jobs, and that became the Lonnie Youngblood thing all over again.” Now leading the band, Youngblood was accompanied by Jimi at gigs on the r&b circuit in New York and Philadelphia. “We used to work the Cheetah (in New York), and we used to work Philadelphia down there on South Street. And the Uptown Theater,” Lonnie recalls, referring to Philadelphia’s equivalent to New York’s famed Apollo Theater. But next on the Youngblood/Hendrix agenda were the famed recording sessions that resulted in sales of over two million copies of the handful of songs in all their varied release formats. Lonnie Youngblood had signed a record deal with Fairmount Records, a subsidiary of Philadelphia’s Cameo-Parkway label. A friendship with Philadelphia club owner Buddy Caldwell led to Youngblood signing with label boss Bernie Lowe’s company, a company that had scored with big pop hits like Chubby Checker’s “The Twist” and Dee Dee Sharp’s “Mashed Potato Time.” The natural assumption, based on the strong Philadelphia connection that Youngblood had, would be that these first ever recording sessions played on by Jimi Hendrix took place in Philadelphia. “No, see, that isn’t true,” Lonnie corrects. “It was in New York, and it was done on eight track at Abtone, Abtone Studio. It was on Broadway, between 55th and 56th, on the second floor. As detailed in the Caesar Glebbeek/Harry Shapiro "Electric Gypsy" discography - and not taking into account the mono/stereo mix variations, overdubs, and length discrepancies that characterize the multitude of releases that contain the Hendrix-Youngblood material - the two musicians collaborated on thirteen tracks over the course of a handful of sessions: “Go Go Shoes,” its continuation, “Go Go Place,” “Soul Food (That’s What I Like),” “Goodbye Bessie Mae,” “Sweet Thang,” “Groovemaker,” “Fox,” and three takes each of “Wipe the Sweat” and “Under the Table.” About the recording sessions that yielded the famed tracks, Lonnie recalls, “It was a blast. But that was all it was going to be because we weren’t making any money! But I always paid Jimi, even if it was only $25 or $30.” As we have seen in the years since those sessions, a multitude of people were well aware that the name “Hendrix” could be cashed in on using the tapes of the Youngblood sessions. But how did the tapes get into distribution? “You see, Fairmount just had a distribution deal - they never had the tapes,” Youngblood reveals. “The tapes were at the studio. Once I’d mixed them down and mastered them, I always left my tapes at the studio because at that time that was the thing to do. When everybody recorded, they left the mother tape at the studio. “These people, they knew where the tapes I had recorded were,” Lonnie continues. “Johnny Brantley was a producer out of New York, and he had a lot of access to a lot of different companies. Like if you cut something and wanted to get it in the door somewhere, maybe Johnny could take it in for you. But he’s a liar and a, what’s the lowest name you can call somebody? The reason I feel this way is because when they took this tape, Johnny Brantley and Joe Robinson, they made a deal with this big company in Chicago, GRP. They went and bribed the guy who owned the studio, and actually went and took my tapes away. And they gave them about $100,000 for this tape. And they took all the money and didn’t give me any of the money. That was my stuff! “And then these companies started to put the shit out and didn’t even put my name on it. They would say it was Jimi Hendrix singing, without my name on it - so many lies, man. The stuff that came out on that album called Two Great Experiences Together! - what happened with that, one company took that and tried to doctor it up to make it have more Hendrix activity. See Hendrix is more or less just backing me up. The companies wanted to say they had a little more activity by Hendrix, so they found some Hendrix wannabees and they put them on the tracks. And what they really did was they messed the tracks up with the overdubs. “The stuff I went through, I wouldn’t wish it on nobody,” Youngblood says. “I was a strange kind of guy - I didn’t think anybody would do that kind of thing to somebody. Which is the dumbest way to be looking at anything, because people will do anything in the world for the sake of a buck. That’s the thing that shocked me more than anything, when I came to the reality of what I was dealing with. It may sound strange to you, but when you talk about the type of people that they were - they were of that caliber, and they were only deceiving the public.” Early in 1964, Youngblood and Hendrix officially parted musical company, but remained friends. Jimi went on to spend much of the year with the Isley Brothers, and then joined up with Little Richard before returning to New York in 1965 and working with Curtis Knight. Meanwhile Lonnie Youngblood was back on the road, opening shows or playing with some of the top manes in soul music. Joe Simon, Sam and Dave, James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Joe Tex, Ben E. King - Youngblood worked with more great acts than he can remember. But the paths of Hendrix and Youngblood continued to cross in the tight New York/Harlem musician scene of the mid-1960s. “When I started recording again, and Jimi Hendrix was on those recordings, he was my guitar player,” Youngblood explains. “But see at the time it wasn’t like that - it may have appeared to be that, because it was my sessions, so I was paying him, and it was my stuff, and the gigs was my jobs and I was paying him. “But, see, everybody was having sessions. As a matter of fact, we were all session musicians. So it wasn’t like recording with a band. Even while I was recording for myself, I was recording solos for other people.” Comments such as this at least bring up the possibility that the lines marking phases of Jimi’s very early New York career may not be as clearly defined as has been accepted. Youngblood even confirms that he himself did some sessions at this time with Curtis Knight for PPX Enterprises at Studio 76 at 1650 Broadway. By June of 1966, though, Jimi had started his own band - Jimmy James and the Blue Flames - and was deeply immersed in the Greenwich Village scene. As the Village was an alien environment compared to the relatively conservative Harlem, it should be no surprise that Lonnie quickly noticed big changes in Jimi when Hendrix paid him a visit. “Jimi knew he wanted to do something different,” Lonnie states emphatically. “He could see where he wanted to go with a new kind of music. He tried to explain it to me and get me to come with him but I couldn’t see what he meant. “See, Jimi had taken and met some friends, and so they were like hippies and stuff, and they liked Jimi,” Lonnie continues. “And Jimi loved to be loved - that was a thing about Jimi. Jimi loved to be loved for being Jimi - he didn’t want you to love him and change him. Because Jimi wasn’t about to change - Jimi wanted to be himself. That’s the way he always was. He may have made a few adjustments from then, but that’s what Jimi was all about. “See, what had happened was that Jimi had tried LSD. Now if he hadn’t done that I might have went with him. He said, ‘Man, we got to try this tab of LSD.’ I said, ’Damn, I was petrified of LSD. I mean, not scared - petrified! Because I heard that LSD would come back on you. So I was scared to death of that stuff, but he was cool. “But he started getting weird, he started talking about different kinds of crazy songs,” Youngblood recalls. “Like ‘The Wind Called Mary’ - he had some other titles at the time, not that one, but they came out on his first or second album. ‘Third Stone From the Sun.’ Anyway, I didn’t go down to the Village with Jimi. Jimi went to the Village and from that Eric Burdon and the Animals flew into the States and were walking around in the Village - because the Village was famous - so they saw Jimi and they were amazed. Because Jimi was awesome - Jimi played a right handed guitar upside down and didn’t miss a note. This guy was unbelievable. So they took Jimi to England. And this guy was adventurous enough to go to England and play - he didn’t give a damn! He was a free spirit, and that’s what I loved about him.” While Lonnie Youngblood labored away at a respectable career, further establishing his reputation in the Harlem scene, Jimi Hendrix began his ascent to stardom. One day in 1967, Lonnie made a shocking discovery. “Jimi was on the charts, and somebody saw his record and came to me and said, ‘That’s your guy!’” Lonnie remembers. He saw the spelling of the name J-I-M-I and didn’t believe it - until he saw the cover of Are You Experienced? Then Youngblood knew it was true. The guitarist who had once backed him was well on his way to revolutionizing rock music and the realm of the electric guitar. But Jimi stayed in contact with Lonnie, occasionally visiting him in Harlem whenever he was in New York. In fact, it’s quite possible that it was one of those visits that Jimi’s friend, Arthur Allen, was referring to when he was quoted in Electric Gypsy saying the following: “Some band was playing and Jimi sat in, but the way he sat in, like he was afraid, like he was wondering if his hat was alright. He really wanted to make a good impression in front of this audience of no more than forty people. But Jimi was very, very self-conscious. And he came in and said, ‘How’s my hat, man, how does my hat look?’ So we said, ‘Your hat looks alright, man.’ ‘Do you think they’ll mind if I?’ Always wondering what we, what other black people thought about his music and him so he wound up jamming and blowing everybody’s freaking mind out every time I seen him play uptown, he played better than I have ever seen him play in my life.” In UniVibes Issue 12 Allen further elaborated Hendrix on that same night by stating, “We went to Small’s one night and he had just bought this guitar, the Flying V.” The club that Allen was speaking of was Small’s Paradise, in Harlem at 138th Street. Small’s was one of Lonnie Youngblood’s main haunts - “It was my headquarters,” he says - and there is a well known photograph of Jimi wearing a hat while playing a Gibson Flying V with Lonnie in 1968. “That’s how we had that very famous picture of me and him on stage together at Small’s Paradise,” Lonnie states. “That’s where I was working.” Based on Jimi’s hat, the presence of the Flying V, and the venue, it’s quite likely that this photo was taken on the very night that Arthur Allen recalled so well. But Jimi’s continuing musical relationship with Youngblood wasn’t limited to jams in clubs. “We hung around for three days down at the Record Plant,” Youngblood recalls. “We recorded for three days - we did not go out of the studio for three days! We were sending out for food, we did everything. We cut enough material for at least two albums.” So what happened to the tapes of this second Hendrix/Youngblood collaboration? “Who knows?” Lonnie reflects. “First of all, he didn’t label the tapes ‘Lonnie Youngblood’ or anything like that. But it was there. And if anybody hears it, I’m doing the singing.” Just before he left America for the last time, Hendrix paid his old friend a final visit - and confided in him the troubles that were on his mind so much of 1970. “He said, ‘Youngblood, there’s a lot of trouble going on. There’s a lot of problems going on and there’s going to be a lot of heads rolling. So when I come back, He was getting ready to start a gospel, pop, blues, and jazz band as a side thing for him that would reach into my situation. He came back for me. “I told him, ‘Jimi, man, if something’s not being done to your own vision, maybe you shouldn’t be too vocal about that until you build up your case and have some legitimacy legally.’ And he said, ‘Man, I’m going to straighten it out.’ And I never saw him again - never saw him alive again.” After Jimi’s death, Lonnie went on doing what he had always done - backing other musicians and leading his own band. And there were new recording sessions such as the ones that yielded single titles like “Super Cool” b/w “Black Is So Bad” and his 1981 Radio/Atlantic Records release Lonnie Youngblood, an album that featured a number of songs written by George Kerr - a name often seen on the myriad of Hendrix/Youngblood releases. Those releases have been a source of mixed feelings for Youngblood. Naturally he is proud of the fact that he was in on the beginning of Hendrix’s historic professional career, but Lonnie also knows that he was taken advantage of financially during a time when it was common for musicians to lose the rights to their own material. “A lot of people that put out that album,” Youngblood reflects. “It came out as Jimi Hendrix and they had Jimi Hendrix on there as the vocalist and some of those albums never exposed me completely, and it was all my stuff! CBS did a big story on that about how they exploited me, and I sued Columbia, and I sued a lot of people. “But they all took advantage of me,” Lonnie continues. “All of them. Nobody paid me. Ohhhh, that’s a whole ‘nother story. That’s heavy. That will bring your anger up because of the way they treated me. You see, I was just a victim of the system and the way things work sometimes, and that’s what happened with that. I don’t run around saying I’m angry about that or anything else, really, because I’m grateful to be alive.” That Youngblood has such an attitude is partially due to the fact that he survived a difficult period of drug abuse. But unlike many musicians who become crippled by their problems, Youngblood became determined to straighten himself out. “I had a problem for about ten years,” Youngblood states frankly. “I got so screwed around with the industry - and I’m not making an excuse for it - that I didn’t give a damn one way or the other. I drugged, man - the only time I felt good was when I drugged, man, because then I didn’t think about it no more. “So about eight or nine years ago I went into Bergen Pines Hospital on rehab,” Lonnie continues. “I got myself together and I never looked back. But that doesn’t mean that just because I’m sober everything’s supposed to just fall into place. Life still goes on - ups and downs and problems and stuff. “But I’ll tell you right now, I’ve had a great career. I’ve worked with every conceivable name, I’ve been to Japan - I’ve gone to Japan twice a year, I’ve worked in Italy, Germany, all of these places I’ve been to on my own. And when I travel with another artist like Ben E. King, we go to different places as well.” Aside from playing with his good friend King - the man whose “Stand By Me” is one of the enduring pop hits of all time - Lonnie Youngblood continues to work hard to take his own career even further. For now, that means recording a blues CD - one track at a time, as finances permit. “There’s so much that’s part of my career,” Lonnie notes. “My career is 45 years - four and one half decades! And you want to hear something funny - it’s still going strong! My blues band is six pieces, the one I’m putting together now. We’re recording and putting the band together - we’re in business. “And naturally there’s financial problems - we’re cutting it piece by piece,” Youngblood explains. “You take a dollar from here and steal a dollar from there. We’ve got about three songs we’ve got now, but it’s long and painstaking.” Youngblood is well aware of the differences between the recording industry of the past and the modern day entertainment media machinery. “Back then all they knew was the finished product,” Youngblood says of the 1960’s. “This is a new day. The rude awakening for me was the fact that you’re not marketable over thirty in the new market. But see, then I discovered that there is a market, and my market is jazz and blues. So I said let me go over to do the jazz and blues thing, so that’s where I’m at. “The blues band is going to be my salvation - you watch and see what I tell you,” Youngblood insists. “See, I should have gone and jumped on the blues before but I didn’t want to be one dimensional. I wanted to do the whole damn thing, I wanted to do pop, I wanted to work on everything. But the blues band is going to bring me into where I’m trying to go. And I know it, because everything’s happening right. Everything is positive and things are happening.” While waiting to complete his blues project, Youngblood plays in clubs and at private functions. Backed by a drummer and keyboard player, Youngblood plays standards like “Take the A Train” and “Mack the Knife” during his sets at Sylvia’s. Standing outside the Harlem landmark, Lonnie notes, “What I’m doing in there I’m doing with just two pieces, and I’m doing it at minimal volume, and I still got to rock them and I got to get their attention.” And “The Prince of Harlem” still has his subjects, as a number of people come up to say hello during a brief photo session on Lennox Avenue outside Sylvia’s. Looking back after more than thirty years have passed, Lonnie remembers fondly the experience of working with Hendrix. “I bought Jimi his amplifier, I bought him one of his first amplifiers in New York,” Youngblood reveals. “Me and my wife spent that money and bought him a Fender amp. He wouldn’t buy an amp - he didn’t give a damn! If you wanted to play with him, you had to buy him an amp! He was that good. Jimi was a light traveler. He didn’t give a damn about no amp - he might have been here today and gone tomorrow! He was like,” Lonnie pauses and laughs, remembering the name Jimi Hendrix worked under in his early New York days. “Jimmy James - he was like a vagabond, man. He was one of the greatest guys I ever had the pleasure of working with.” The legend of Jimi Hendrix will be forever linked with the name Lonnie Youngblood - and with those historic recording sessions in New York in 1963, when the guitar artistry of Jimi Hendrix was first recorded and released on record. With a smile, Lonnie Youngblood sums up his feelings about it all. “I’ve sold over two million copies of that Jimi Hendrix album. So, I didn’t get any finances from it - but I’m always known.” |

|

|

|

|